There has always been much debate surrounding the idea of “foreign occupation” in Haiti. Haitians, of course, are opposed to this. And some Haitian leaders capitalize on this opposition by distorting the facts and not taking the responsibility for requesting this support – or, more importantly, contributing the environment where such a need becomes imperative. The fact is that from 1990 to present, the United Nations has deployed at the request of the Haitian government 14 missions to Haiti:

Technical assistance requested by president Ertha Pascale Trouillot in 1989 to support the elections

Request for an economic embargo against

Haiti by Jean Bertrand Aristide in 1992

Aristide request for MICIVIH February 1993 – May 1998

U.S. Military intervention requested by Aristide in 1994

UNMIH September 1993 – June 1996

UNSMIH July 1996 – July 1997

UNTMIH August 1997 – November 1997

MIPONUH December 1997 – March 2000

MICAH March 2000 – Feb. 2001

Aristide request to the Clinton Administration for military intervention in 2000

Aristide request to the Bush Administration for military intervention January 2004

Aristide request to the United Nations in January 2004: MINUSTAH April 2004 – Présent

Aristide request to OAS 2000 – 2007

Aristide request to CARICOM 2001 – 2004

The United Nations in Haiti has spent millions of dollars over the past seventeen years deploying peace keeping missions -- with nothing to show for it (see The International Aid Debacle @ http://solutionshaiti.blogspot.com/2007/01/international-aid-debacle-how-to-get.html ). Clearly, their strategy has not been effective, or there would not be a continuing need for such intervention. One of the major reasons for this is: they are not really building capacity. Rather, they are doing the work themselves. They run elections for Haitians, conduct police operations themselves, openly promote the amendment of the Haitian constitution, and reform of the judicial system. This is a mistake. It goes against the old adage of “teaching a man to fish” and against the basic principles of nation building.

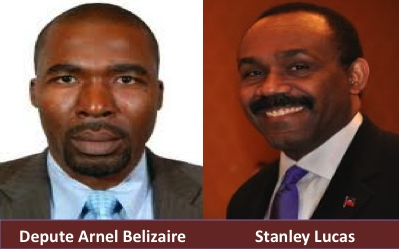

If MINUSTAH is to be successful in Haiti and leave behind strong and democratic institutions, they must revise their current strategy in the light of the Nine Principles of Development and Reconciliation written by Andrew Natsios. The United Nations and the Organizations of American States need to strengthen their working relations. The offices of the Secretaries General of the OAS and the UN should create an independent, non-partisan commission to conduct a quarterly evaluation of the performance of the missions, the Haitian government, and the perception of the Haitian people, civil society and political parties. Such commission could be comprised of former U.S, Canadian, Caribbean and European Government officials and Haitians living abroad with strong records of accomplishment of political development success. In this way, we could ensure an honest assessment of the current situation and allow for corrections in the mission plans before we continue to waste time and energy on ineffective tactics. Stanley Lucas------------------------------------------

The Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development -----

ANDREW S. NATSIOS

Autumn 2005

The US foreign assistance community is in the midst of the most fundamental shift in policy since the inception of the Marshall Plan at the end of World War II. The events of 11 September 2001 suddenly and unexpectedly forced the United States to confront a historic challenge equal in magnitude to the Soviet threat of the Cold War. The tragedy initiated a series of changes leading to the most extensive government reorganization since the Truman Administration created the National Security Council and the Department of Defense. No agency has undergone a greater degree of internal review and transformation than the US Agency for International Development (USAID). For better or worse, USAID is on the front lines of the dominating news stories of the day, whether engaging in reconstruction work in Afghanistan or providing tsunami relief in South Asia. This renewed prominence is not an accident. On the contrary, President George W. Bush’s Administration has made development work a national security priority; the September 2002 National Security Strategy underscores development as one of three strategic areas of emphasis (along with diplomacy and defense), and clearly states that “including all of the world’s poor in an expanding circle of development—and opportunity—is a moral imperative and one of the top priorities of US international policy.”1

This new development climate has brought about internal recognition in the agency that it requires a more uniform and consistent set of guiding principles, and that these principles must accurately reflect how USAID approaches development from all levels—from day-to-day project operations to high-level policy decisions. Drawing on more than 40 years of institutional development experience and building on a series of recent policy strategies,

including U.S. Foreign Aid: Meeting the Challenges of the Twenty-first Century and the Fragile States Strategy,2 this article presents the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development, comprising ownership, capacity building, sustainability, selectivity, assessment, results, partnership, flexibility, and accountability.

The purpose of this article is to introduce and analyze the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development to the military community. In a time of increasing collaboration between the two organizations, it is important that the military gain a better understanding of how USAID and development agencies generally approach their work, and how the two communities can beneficially build on this cooperation. This article specifically incorporates project-level examples from Afghanistan to better illustrate and provide context for the Nine Principles. Afghanistan is not presented as an ideal development context in which to apply the principles, but it demonstrates how they may apply even in fragile, less-stable environments. Ultimately, the article contends that the Nine Principles are integral to reconstruction and development success. When a foreign assistance agency adheres to the Nine Principles, this greatly enhances the likelihood of success. Conversely, failure to take the Nine Principles into account when designing and managing a program increases the risk of program failure.

Just as a particularly skilled battlefield commander can violate one or two of the principles of war and still prevail, a development officer may violate one or two of the development principles and still succeed. But generally development agencies ignore these principles at great risk, particularly in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Sudan, where major reconstruction efforts are under way. ---------------------------------------------------------------

Background

There are a number of different ways to approach international development. USAID’s White Paper on Foreign Aid enumerates five core development goals: promote transformational development, strengthen fragile

states, provide humanitarian relief, support US geostrategic interests, and mitigate global and transnational problems.3 Overall, USAID is the leading US government agency responsible for promoting peace and stability by fostering economic growth, protecting human health, providing emergency humanitarian assistance, increasing literacy, and enhancing democracy in developing countries.

The origins of USAID and the modern US development discipline can be traced to the end of World War II. Top policymakers of that era realized that traditional American isolationism was no longer a tenable strategy and argued for a new approach. The cornerstone for this policy shift occurred on 5 June 1947, when Secretary of State George C. Marshall gave a commencement address at Harvard University and advocated that the United States use its power and wealth to nurse a world devastated by war back to “economic health.”4 This speech gave rise to the Marshall Plan and formed the historical foundation for USAID (the agency was officially established in 1961 by executive order of President John F. Kennedy, combining three existing agencies).

The evolution of US foreign assistance policy is now in its most critical stage since the Marshall Plan. The strategic goals outlined in the National Security Strategy confirm that a new development paradigm has emerged: USAID no longer operates on the periphery of US foreign policy. Instead, there is a broadening recognition that the agency and development work in general are vital to US national security interests.

One implication of elevating development work as one of the three pillars of national security is increased collaboration between the military and development communities. Situations like Afghanistan and Iraq—which require a broad-based, coordinated humanitarian response—are becoming increasingly common. More significantly, the success of military strategy and the success of development policy have become mutually reinforcing. Development cannot effectively take place without the security that armed force provides. And security cannot ultimately occur until local populations view the promise of development as an alternative to violence. Moreover, while the military is well placed to undertake certain types of stabilization projects, civilian agencies can relieve the military of many reconstruction and development projects which it is not well suited to oversee. Thus, it is important that the military gains a clearer understanding not only of how USAID implements a project or operates a field mission, but a deeper grasp of the core principles the agency follows when approaching all development work.

At a basic, theoretical level, the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development are inspired by the Nine Principles of War, which are inscribed in modern Army field manuals.5 In the past decade, the military has attempted to forge a closer theoretical link between post-conflict development work and military interventions. In the mid-1990s, it established the six principles of Military Operations Other Than War (MOOTW), which served as an initial bridge between the two disciplines. More recently, especially since 9/11, there has been a growing recognition that conflict should be defined in more fluid terms; that the line between formal military engagement and informal insurgencies is increasingly blurred. As a result, military thinking has evolved and now incorporates the phrase “stability operations” as a term of art to describe post-conflict nation-building efforts.6 Despite this shift, the military continues to use the Nine Principles of War as an intellectual basis for all military operations, including stability operations (it has folded the six principles of MOOTW into the Nine Principles of War rubric). The Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development have evolved from a similar institutional experience. They distill fundamental lessons from this experience and bring greater clarity to the operative principles that inform the mission of USAID. --------------------------------

Principle 1: Ownership

Build on the leadership, participation, and commitment of a country and its people.

The first principle of development and perhaps the most important is ownership. It holds that a country must drive its own development needs and priorities. The role of donor organizations is to support and assist this process as partners toward a common objective.7 It is essential that the country’s people view development as belonging to them and not to the donor community; development initiatives must meet the country’s needs and its people’s problems as they perceive them, not as distant policymakers imagine them. Nurturing country ownership is a laborious process that emerges with time and effort. It requires a strong agency ground presence in order to build credibility, trust, and consensus in the local population.

What the people of a community want ultimately counts a great deal, since their community belongs to them and not to external aid agencies. When ownership exists and a community invests itself in a project, the citizens will defend, maintain, and expand the project well after donors have departed. If what is left behind makes no sense to them, does not meet their needs, or does not belong to them, they will abandon it as soon as aid agencies leave. It does take much longer to engage national and local leaders patiently in their own development than to simply impose it from the outside quickly and autocratically, but the result makes all the difference.

US policy in Afghanistan has emphasized the ownership principle and has focused on encouraging Afghans to take government leadership positions. The selection of Hamid Karzai as President of Afghanistan is a good

illustration. In December 2001, the four major Afghan factions met in Bonn, Germany, to select an interim leader. They subsequently chose Karzai to head the Afghan Transitional Authority. What is significant about this model is that Karzai is Afghan and his ministers are all Afghan-born as well.8 Karzai has additionally strived for ethnic balance; the interim cabinet comprehensively represented all the various political groups in Afghanistan, from Mujahiddin and Northern Alliance factions to European and American members of the Afghan Diaspora.9

It is important to have a national lead the country and to have nationals head the ministries for several reasons. First, selecting a national as head of state provides a much greater degree of legitimacy; the Afghan community will inherently trust and relate better to an Afghan leader than to an outsider running the country. Second, having an Afghan leader eliminates the language barrier. Documents and meetings do not have to be translated, and general communication is facilitated. Third, it is vital that Afghans run the government transition process themselves; this may be more chaotic in the short-term, but it also means that Afghans will own the process and ultimately be responsible for the choices they make. Fourth, an Afghan such as Karzai understands the nuances of the political situation better than any outsider and is more capable of navigating through problems as they arise. Finally, when attempting to win the “hearts and minds” of the local population, especially in the midst of Taliban and warlord turmoil, it is essential to mobilize the Afghan people behind the government’s policy. One of the most important factors responsible for the growing stability and prosperity of Afghanistan is this successful mobilization of the great bulk of the population behind national government policies. This is best accomplished by an Afghan leader. ---------------------------------------

Principle 2: Capacity Building

Strengthen local institutions, transfer technical skills, and promote appropriate policies.

Capacity building involves the transfer of technical knowledge and skills to individuals and institutions so that they acquire the long-term ability to establish effective policies and deliver competent public services. One of its most important by-products is that the country increases its ability to retain, absorb, and facilitate economic investment, whether from donor assistance or from private sources of Foreign Direct Investment. Ultimately, an improved governance and investment environment is a necessary condition for sustained economic growth in any country.

The development community recognizes that the right government policies underscore all successful development efforts. Simply put, a country

with weak governance institutions and misguided policies will have a limited ability to lead its own economic and social development. For example, it is not enough to build universities and educate a country’s population. This effort must be accompanied by direct opportunities that will allow university graduates to become future political and business leaders.

Capacity building applies in the military context as well. For example, in Afghanistan the US military has established the Kabul Military Training Center as part of a $750 million plan to prepare and train a national force “capable of replacing the militias” that drove out the Taliban in 2001.10 The expectation is that the US military will transfer necessary technical skills to the Afghan National Army (ANA), which will gradually assume full responsibility for the country’s security needs.

Among the most important capacity building activities that USAID implements in Afghanistan are education programs; these are the building blocks that will foster the next generation of Afghan doctors, lawyers, engineers, and technocrats. Capacity building has occurred in several different forms. On one level, USAID has directly improved the performance and functioning of the Ministry of Education by providing technical and management advisers, assisting with curriculum development workshops, and ensuring that the ministry can manage textbook printing requirements in future years.11 On another level, USAID has built individual teacher capacity through programs such as the radio-based teacher training (RTT) program, which targets teachers who reside in remote areas of the country. As of June 2005, some 65,000 teachers have been trained through broadcasts that strengthen their teaching skills and spread civic and educational messages. About 7,500 more teachers have been trained through face-to-face instruction, and 6,800 in an accelerated training program.12 As more teachers have been trained, more children have returned to school: primary school enrollment has increased from a pre-war total of one million (2001) to 4.8 million as of December 2004.13

The development community accepts the notion that strong human and technical capacity are necessary prerequisites for stability and economic growth. Simply put, a country with weak government institutions staffed by unqualified and inefficient officials will have a limited ability to lead and sustain its own economic and social development. ------------------------------

Principle 3: Sustainability

Design programs to ensure their impact endures.

The core of the sustainability principle is that development agencies should design programs so that their impact endures beyond the end of the project. Sustainability also encompasses the notion that a country’s resources are

finite and development should ensure a balance between economic development, social development, and democracy and governance. The sustainability principle forces aid managers to consider whether the technology, institution, or service they are introducing to a society will have a lasting effect.

Sustainability is equally applicable in the military context. In order for the military to accomplish its missions, commanders must persevere; they must balance the need to quickly execute their immediate mission and then depart, on the one hand, with the necessity of developing sustainable local police and military forces capable of protecting the country in the future against resurgent Taliban or al Qaeda forces, on the other.14 For example, it is not enough for the US military to train and initially equip ANA soldiers. The best-trained army will languish and deteriorate without ongoing government support and funding. Sustainability demands that the Afghan government eventually start replacing external military assistance with domestic tax revenues to fund the Afghan National Army and other public services.

Sustainability is especially important in times of turmoil; if proper sustainable structures are in place, then the project will endure despite surrounding conflict. A good case in point is the Kajaki Dam in Afghanistan. The dam was originally constructed in 1953 with funding from the US Export-Import Bank; it was upgraded with USAID assistance in 1975.15 It has supplied continuous electricity to the provinces of Helmand and Kandahar and consistently provided irrigation water to the surrounding valley. After the invasion of the Soviet army in 1979 and the subsequent withdrawal of US assistance to Afghanistan, the engineers in charge of its maintenance were able to keep the dam operational and productive through 23 years of civil war and Taliban oppression without any external assistance, supplies, or funding.16 The dam’s remarkable sustainability has been due to a combination of factors: extensive engineer training that emphasized dam maintenance, durable construction design, and adherence to the ownership principle—Afghans took responsibility for maintaining the dam themselves, and they did everything possible to keep it operational.

In contrast, other development efforts in Afghanistan have been less successful because they have failed to take the sustainability principle into consideration. For example, one outside agency intended to provide electricity to a remote village. Rather than extend power lines from a central grid, they supplied a diesel generator. In the short-term, the village had an ample source of electricity. In the long-term, this proved unsustainable as the village had no means or resources to replenish the spent fuel and lacked the technical ability to repair the generator as required. Sustainability means ensuring that the program’s impact will endure. It entails, for instance, making certain that a nearby aquifer can adequately support the local population’s long-term water needs before tapping the source and constructing a water system.

Ownership, capacity building, and sustainability form an iron triad of principles underscoring all successful and enduring development and reconstruction projects. These principles cannot be applied successfully over short time periods. They require years of consistent effort and support or they will fail. There are no quick fixes in successful development. A development officer ignores these principles at great risk: alienation of the local population and failed projects. ----------

Principle 4: Selectivity

Allocate resources based on need, local commitment, and foreign policy interests.

The selectivity principle directs US bilateral assistance organizations to invest scarce aid resources based on three notions: humanitarian need, the foreign policy interests of the United States, and the commitment of a country and its leadership to reform. To maximize effectiveness, donor resource allocation must be targeted where it can have an appreciable impact and where the recipient community demonstrates commitment to development goals.

In military terms, selectivity closely relates to the principle of “mass”—concentrate military power at the decisive place and time. The underlying notion is that resources are finite and are most effective when concentrated together in select situations. Any allocation of resources, whether in combat operations or infrastructure projects, must take into consideration foreign policy interests, political circumstances, and ground-level need.

President Bush’s Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) exemplifies the principle of selectivity. The MCC is not meant to provide everlasting across-the-board economic growth assistance. Instead, it focuses on transformational development, fostering far-reaching, fundamental changes so that further economic and social progress can be sustained without dependence on foreign aid. Thus, the MCC applies to a specific country archetype: one that possesses a strong governance framework and which requires large-scale capital investment as a final ingredient toward full-scale development and growth. To determine which countries fit this transformational development model, MCC rates countries on a 16-point scale in the broad categories of ruling justly, investment in people, and economic freedom. It then selects countries eligible for funding based on a country’s rating.

In Afghanistan, the restored Kabul-to-Kandahar highway illustrates the selectivity principle.17 More than 35 percent of the country’s population lives within 50 kilometers of this highway; unfortunately, over two decades of war and poor maintenance had devastated the road.18 Restoration of the highway was a high priority for President Karzai and President Bush: USAID was asked to implement the project over a short time frame of 14 months. The project was crucial to extending the influence of the new government; the road has led to increased rates of economic development, it has fostered civil society, and it helps ensure unity and long-term security in the country.19 In addition, the road circulates through a significant number of Taliban strongholds, so upgrading the road has diminished the Taliban’s ability to exert influence in this portion of the country.

The highway is a primary example of the selectivity principle. USAID factored in the developmental need the highway would serve (access to markets and cities), the foreign policy interests of the United States (promote economic development and country unity, counteract Taliban influence), and the commitment of a country and its leadership to reform (President Karzai is an acknowledged reformer with exceptional commitment to the project). ------------

Principle 5: Assessment

Conduct careful research, adapt best practices, and design for local conditions.

One of the most important tasks a development agency must undertake before designing and implementing a program is to conduct a comprehensive assessment of local conditions. A development agency must consider several factors in the assessment process: Do reconstruction plans conform to conditions on the ground? What are the best practices for each intervention? And what is the absorptive capacity of a society to accept large amounts of assistance? (One of the most serious failures of foreign aid programs is to force too much money into local institutions that cannot responsibly spend the increased external funding.) Beginning a program without proper assessments is comparable to initiating a major military campaign against a determined adversary with no military intelligence: it is a recipe for failure.

USAID’s collaboration with the Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in Afghanistan—which are joint civil-military units, each consisting of 70-80 personnel—offers another illustration of the assessment principle. Good development demands that an agency conduct ground-level assessments before enacting a project. In select situations, USAID makes use of the PRTs because they allow civilian personnel to conduct field assessments in areas that are otherwise unstable because of the presence of Taliban insurgents, regional warlords, drug-financed criminal organizations, and an atmosphere of general lawlessness.20 USAID has been able to monitor critical reconstruction projects, conduct needs assessments, and mobilize local partners with support from PRT military forces.

Further, in conjunction with the PRTs, USAID must ensure that a proposed project fits into national ministry plans. One of the primary responsibilities of a democratically elected government is to provide essential and needed public services; doing so builds public support and loyalty to the government. To facilitate this, each ministry in Afghanistan has produced a strategy which fits into the Afghan national development plan to ensure that limited resources are maximized—for example, ensuring that new schools are built in underserviced communities that lack educational facilities. For a project to be effective, a donor must make certain that a potential school not only is included in the ministry’s strategic plan, but that the ministry has budgeted funds to support teachers, staff, and textbooks for the school.

Without a comprehensive field-level assessment, it is almost impossible to predict whether a project will have a measurable and definable effect. The principle of assessment is linked closely to the next principle of development—results.

Principle 6: Results

Direct resources to achieve clearly defined, measurable, and strategically focused objectives.

The principle of results is an outgrowth of the assessment principle. It means that before a donor agency even enters a particular country, it first determines its strategic objectives: What impact do the donor and the country hope to achieve? Second, the donor and country must consider how they can best attain the desired impact: What types of programs and resources will lead to the goal? Finally, the donor and the country must determine what specific benchmarks will indicate whether they are accomplishing their strategic objectives and whether implemented programs are achieving the intended impact.

USAID incorporates the principle of results throughout all its programs and operations in over 80 countries in which it has field missions. The rationale underlying this principle is that when an agency is obligated to consider programmatic impact from the beginning stages, this will lead to more clearly defined and strategically focused objectives. Since 1993, the notion of managing for results has emerged as an explicit core value of the agency. When deciding whether to implement a particular project, the agency applies a “results framework” that visually depicts the objectives to be achieved by USAID and through the contributions of other donors and actors.

Likewise, the results principle is equally integral to military science. The principle of the objective directs that “every military operation should move toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective,” and that officers must understand strategic aims, set appropriate objectives, and ensure these objectives contribute to overall unity of effort.21

Two examples of USAID’s reconstruction and development work in Afghanistan demonstrate the results principle in practice:

• It is vital that Afghanistan establish a legitimate and democratic government if it is to achieve a lasting measure of political stability. To assist in that objective, USAID supported the government of Afghanistan in its October 2004 presidential election. Over 11 million Afghan-born voters registered in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. USAID supported the hiring and training of approximately 120,000 polling workers by the national election commission, and it provided support in setting up 22,000 polling stations and 5,000 polling centers. On the 9 October election day, approximately eight million Afghans voted, 41.3 percent of whom were women.22

• Instability, coupled with the region’s four-year drought, had devastated Afghanistan’s food production capacity. In response, USAID established the Rebuilding Agricultural Markets Program (RAMP), which focuses on all aspects of the agricultural sector, including such elemental requirements as providing seeds and fertilizer, rebuilding rural roads and bridges, improving access to markets, vaccinating livestock, and extending micro-credit lending. To date, RAMP has assisted 588,000 farmers, and has vaccinated 2.3 million livestock per quarter. Its microfinance component has disbursed more than $700,000 in loans to some 9,500 borrowers. The program has improved irrigation in more than 840,000 acres and established 17 village-based seed enterprises, producing an estimated 4.3 million metric tons of cereal crops for 2005.23

The National Security Strategy emphasizes that the United States must “insist upon measurable results to ensure that development assistance is actually making a difference in the lives of the poor.”24 The principle of results reinforces this sentiment by requiring development agencies to focus attention on the actual impact of foreign assistance investment. -------------

Principle 7: Partnership

Collaborate closely with governments, communities, donors, non-profit organizations, the private sector, international organizations, and universities.

The partnership principle is a central element of USAID’s business model and holds that donors should collaborate closely at all levels with partner entities, from local businesses and private voluntary organizations to government ministries.25 When USAID implements a project, it usually works with a network of partners; this could include an international nongovernmental organization (NGO) which will exercise direct oversight over an entire program, or a local university that will implement a civic education initiative.

USAID’s structure varies significantly from the military’s organization. The agency uses a highly decentralized structure where implementation and much program design takes place in country field missions. The USAID equivalent of “commanders” is its “mission directors,” and they have much greater autonomy than counterparts in the military and most other international aid agencies. USAID missions work in a linear, horizontal organizational structure that links various voluntary partnerships, many different parts of civil society, and local and national governments, through voluntary agreements and funding mechanisms.

An important part of the agency’s mandate in recent years has been to expand its base of partners and use nontraditional groups who have much to offer to the development community. This includes opening a faith-based office to accommodate these new, nontraditional groups, and extending its partner outreach to the business community, working through the auspices of the Global Development Alliance. To date, USAID has signed more than 285 collaborative agreements, contributing $1.1 billion and leveraging another $3.7 billion in private funding, designed to facilitate work with nontraditional partners such as foundations, private universities, and private corporations.

The partnership principle is a significant component of USAID projects in Afghanistan. One example is the agency’s work with media programs and radio broadcasters. Radio predominates in Afghanistan; during the war it was the lifeline for a scattered population, most of whom cannot read. In a broadcasting environment that had been tightly controlled by the state and Afghan warlords, where the Taliban had banned the playing of music, it was important to promote a free and open media and to build a society tolerant of free expression. To that end, USAID has provided capital and training in message delivery to 32 radio stations throughout Afghanistan, including a commercial radio station network run by Afghan repatriates.26 This network targets the youth audience of Kabul and other major cities through determined work, willingness to take risks, and financial contributions from its Afghan proprietors. One station owner states, “We identified a target market of 15- to 40-year-olds. This is the generation that’s going to have a huge impact on the future of this country. . . . Elitists think you should tell people what’s good for them and what’s not good. But we do the opposite—we give them what they want.”27

When contemplating a project, one of the first things the agency looks for on the ground is a strong, local partner who can effectively manage the program from design and assessment to implementation. The agency has developed a set of analytical tools to determine which potential partners have the highest likelihood of success. ------------------------------------------

Principle 8: Flexibility

Adjust to changing conditions, take advantage of opportunities, and maximize efficiency.

Development assistance is fraught with uncertainties and changing circumstances that require an agency to continuously assess current conditions and adjust its response appropriately. Often, small windows of opportunity appear out of nowhere—for example, a sudden change in top leadership—that can critically affect donor strategy. The principle of flexibility maintains that agencies must be adaptable in order to anticipate possible problems and to take advantage of unforeseen opportunities. On the other hand, flexibility must be balanced with the fact that good development takes time—nations are not built overnight, but require continued effort. In the past there has been little inclination to spend sustained amounts of money for long-term reconstruction. The Bush Administration has adopted a new approach, especially with regard to Afghanistan. This has allowed reconstruction efforts to be systematized and done on a large scale.

Flexibility and the principle of maneuver are integral components of military stabilization operations as well. Because political considerations guide stabilization efforts, military commanders must remain constantly aware of the political environment and be prepared to change tactics accordingly. Moreover, the fact that stabilization operations incorporate such an expansive agenda—encompassing everything from anti-terrorist exercises to humanitarian assistance—underscores the need for military flexibility.

USAID’s role in the Afghan counternarcotics program illustrates the importance of being responsive and flexible. In 2004, poppy production in Afghanistan expanded to more than 500,000 acres, resulting in the opium economy accounting for 60 percent of Afghanistan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In response, USAID was asked to create the Alternative Livelihoods Program, which provides Afghans with short- and long-term sources of income in order to help farmers move out of the poppy economy and into legitimate agricultural activities. Rural development programs already are an integral part of USAID’s agriculture strategy; consequently, the agency was able to refocus the current agriculture program in order to assist and tackle the poppy problem. By investing additional resources in existing rural growth programs, focusing on both farm and non-farm employment, and building upon its relationships with local governments in targeted poppy-growing areas, USAID is leveraging the Afghan government’s commitment to fighting the opium problem.28 USAID’s experience in alternate livelihood programs in cocaine-producing areas of Latin America suggests they can be successful only if combined with aggressive eradication and interdiction programs. In a recovering state, such as Afghanistan, the ability to move quickly and react flexibly as urgent situations arise is essential. --------------------------------------------------------------------

Principle 9: Accountability

Design accountability and transparency into systems and build effective checks and balances to guard against corruption.

There are two important aspects to the accountability principle: donors should work to fight corruption in the countries where they operate, and donors must also ensure that the actual programs they implement are transparent and accountable. Within the US government, oversight bodies such as the Inspector General, independent auditors, the Government Accountability Office, and congressional investigative committees help guard against cost overruns, financial abuse, and contractor mismanagement. Externally, development agencies should ensure that potential projects are not preyed upon by corrupt local officials, and that development programs enhance democratic governance structures and local accountability systems. Political institutions—especially in developing countries—are fragile, and if these countries lack a strong rule-of-law foundation then there is an increased risk of corruption.

The accountability principle closely relates to stabilization operations as well. The local population must view the military operation as legitimate, and they must also perceive that their government has real authority. If corruption takes root, either on the side of the US aid program or on the part of the host-country government, then the entire principle of legitimacy is undermined.

In the case of a fragile state such as Afghanistan, applying the principle of accountability is even more important. In such states, the risk of diversion of funds and of corruption is extremely high. Three operating disciplines have been used in managing programs which have protected projects from corruption. First, the agency has built-in accountability procedures in its business model: its procurement and implementation procedures are statutorily regulated by the Federal Acquisition Rules, and offices such as the Inspector General perform concurrent audits while the programs are being implemented to ensure compliance. Second, the agency has limited prime contracting to major international firms (local firms frequently do not have the capacity to manage major infrastructure projects), but it has ensured that the selected firm subcontract to Afghan construction companies. Third, the agency has supported the Afghan Ministry of Finance to implement a number of anti-corruption programs, including an extensive customs reform program. In the last fiscal year, such programs enabled customs to exceed its budget target by 20 percent, constituting about half of all domestic revenue.29

The Kabul-to-Kandahar road project again is a good illustration of the first two factors in practice. USAID selected the prime contractor, which in turn subcontracted various pieces to local firms. For purposes of accountability, the agency built in several layers of oversight. First, the agency has an in-country engineering staff that performed quality assurance inspections of contractor work and which operated as watchdogs over the entire process. Second, USAID’s Inspector General consistently reviewed financial invoices and conducted two general audits to ensure regularity and compliance. Third, the agency contracted with the US Army Corps of Engineers to provide technical oversight functions over the contractor. The result was that the project finished to specification and on schedule.30

Based on its institutional experience, USAID follows a standard set of accountability guidelines. It distributes smaller amounts of money to local organizations to avoid overwhelming underdeveloped systems. It disburses funds only after work on a project run by a new local organization is complete or as bills arrive. The agency seldom provides up-front money to untested implementing organizations. Further, the agency provides significant financial system training to local groups to build their capacity to handle larger sums of money. Finally, USAID compiles a list of corrupt organizations and bars them from receiving future funding. Finally, the agency chooses experienced organizations as primary fiduciary agents in order to facilitate timely and accountable completion of large-scale projects. --------------------------------

Conclusion

The Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development are a formalization of customary USAID operating procedures. They reflect key institutional principles that most seasoned aid agencies incorporate in all their work, from ensuring local ownership and sustainability of a health clinic to flexibly adjusting a rural development program to counteract poppy cultivation.

The tragic events of 11 September 2001 ushered in a new development and security paradigm; the implications have been far-reaching, and they extend through all branches of the US government. This new paradigm means that an increasing number of complex emergencies and fragile states have heightened consequences for US national security interests. It is no longer acceptable or appropriate for us to avoid engaging with failed states; there is a contemporaneous correlation between failed states and terrorist-induced instability. The development community and the military community will continue to move toward closer and increased collaboration. Already, we are witnessing the emergence of this shift in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is critically important that the military and development communities achieve a better understanding of each other’s comparative advantages and collaborate accordingly. For example, while the military is the best instrument to enter a conflict environment and provide an immediate stabilizing force, civilian agencies are better equipped to oversee actual reconstruction and development work.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind two notions regarding the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development. First, the Nine Principles significantly overlap with military doctrinal principles. The continued development of the military’s stabilization operations platform and the increasing frequency of civil-military collaborations means this convergence is here to stay. Second, effective reconstruction and development work cannot afford to overlook the Nine Principles. Quite simply, reconstruction is not effective when the local population does not feel a sense of ownership toward donor programs. Likewise, if donors ignore the accountability principle, not only does this set a poor example for the local population, but the legitimacy of the donor’s overall involvement is brought into question. The development discipline will continue to evolve as will our understanding of it; the Nine Principles are an important part of this continuing effort. ----------------------------------------------------

NOTES

1. George W. Bush, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington: The White House, September 2002), p. 21, http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss.pdf.

2. US Agency for International Development, “White Paper: U.S. Foreign Aid, Meeting the Challenges of the Twenty-first Century,” January 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/policy/pdabz3221.pdf (hereinafter, “White Paper”); US Agency for International Development, “Fragile States Strategy,” January 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/policy/2005_fragile_states_strategy.pdf.

3. “White Paper,” p. 5.

4. George C. Marshall, “Commencement Address at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, June 5, 1947,” http://www.usaid.gov/multimedia/video/marshall/marshallspeech.html.

5. US Department of the Army, Operations, Field Manual 3-0 (Washington: GPO, 14 June 2001), para. 4-33, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/fm/3-0/ch4.htm. In the 19th century war came to be studied scientifically. Carl von Clausewitz was among the first to analytically examine war in his landmark treatise, On War. The Nine Principles of War are a result of this ongoing inquiry. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1976).

6. Stability operations are: “military operations in concert with the other elements of national power and multinational partners, to maintain or re-establish order and promote stability.” US Joint Staff, “Joint Operations, Concepts,” 3 November 2003, http://www.dtic.mil/futurejointwarfare/concepts/secdef_approved_jopsc.doc.

7. This article uses the terms “donor organization” and “donor agency” to refer to those entities that provide direct funding for development activities. Other examples of donor agencies include the World Bank, UN agencies, International Monetary Fund, and UK Department for International Development.

8. US Agency for International Development, “OTI Country Programs, Field Report: Afghanistan,” January-February 2002, http://www.usaid.gov/hum_response/oti/country/afghan/rpt0202.html.

9. “Hamid Karzai Names a New Government,” Economist, 1 January 2005.

10. US Agency for International Development, “Afghanistan Reborn,” October 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/AfghanistanReborn.pdf.

11. US Agency for International Development, “Afghanistan: Enhancing Education,” 18 July 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/education.html.

12. Ibid.

13. The Brookings Institution, “Afghanistan Index,” 23 March 2005, http://www.brookings.edu/dybdocroot/fp/research/projects/southasia/afghanistanindex.pdf.

14. US Army, Stability Operations and Support Operations, Field Manual 3-07 (Washington: GPO, February 2003), pp. 1-19 to 1-20.

15. Louis Dupree, Afghanistan (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1980), p. 484.

16. US Agency for International Development, “Rebuilding Afghanistan: Weekly Activity Update,” 2-10 February 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/weeklyreports/021004_report.pdf.

17. The selectivity principle is instrumental in determining the amount of reconstruction assistance appropriated to Afghanistan. From 11 September 2001 through the end of Fiscal Year 2004, USAID has provided approximately $2 billion in humanitarian and reconstruction assistance. Funding appropriation levels were $279.4 million in FY 2002, $356.3 million in FY 2003, and approximately $1.07 billion in FY 2004. Official Development Assistance totals reflect a similar increase in assistance: $7.7 million in 2001, $367.61 million in 2002, and $485.79 million in 2003. The rationale for this large investment is that after 23 years of conflict and suffering, the country only now has a reform-minded government in place and the beginnings of a democratic system. Thus, an infusion of development resources has the potential to bring about critical and decisive change. US Agency for International Development, “FY 2005 USAID Country Summary Allocation – Request,” http://www.usaid.gov/policy/budget/cbj2005/pdf/fy2005summtabs4_alloc.pdf; “International Development Statistics Online Databases on Aid and Other Resource Flows,” 2005, http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/idsonline.

18. US Agency for International Development, “Rebuilding Afghanistan: Road to Success,” 27 February 2003, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/RoadtoSuccess.pdf.

19. Ibid.

20. US Agency for International Development, “Rebuilding Afghanistan, Weekly Activity Update,” 11-16 February 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/weeklyreports/021604_report.pdf.

21. Field Manual 3-07, pp. 1-19.

22. Afghanistan Presidential Election Results, Joint Electoral Management Body Secretariat, July 2005, http://www.elections-afghanistan.org.af/Election%20Results%20Website/english/english.htm; US Agency for International Development, “Rebuilding Afghanistan, Weekly Activity Update,” 30 September - 4 November 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/weeklyreports/110304weeklyreport.html.

23. US Agency for International Development, “Afghanistan, Restoring Agricultural Markets,” 18 July 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/agriculture.html.

24. Bush, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America, p. 22.

25. USAID’s development partners can be broadly broken down into several different categories. At one end, the agency collaborates with bilateral and multilateral donor organizations. This includes United Nations agencies, such as UNICEF and UNHCR, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, and traditional bilateral entities such as the UK’s Department for International Development. Donors rarely implement projects; they tend to work with different organizations which directly manage the projects. These implementing organizations vary widely, including private voluntary organizations, indigenous groups, universities, local and American businesses, other governments, trade and professional associations, and faith-based organizations.

26. US Agency for International Development, “Afghanistan Transition Initiative: Media,” February 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/briefer_oti_media_0205.pdf.

27. Quoted in Victoria Burnett, “Trendy Radio Station Strikes Chord with Youth, Financial Times, 7 September 2004.

28. US Agency for International Development, “Drug Eradication Program in Afghanistan,” 22 October 2004, http://www.usaid.gov/locations/asia_near_east/afghanistan/drugeradication.html.

29. International Monetary Fund, Concluding Statement of the IMF Mission, 18 May 2005, http://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2005/051805.htm. Fighting corruption is such a priority for the agency that it released a comprehensive anti-corruption strategy at the beginning of 2005 reflecting five years of discussion and analysis. See US Agency for International Development, “Anti-corruption Strategy,” January 2005, http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/democracy_and_governance/publications/pdfs/ac_strategy_final.pdf.

30. US Agency for International Development, “USAID Fact Sheet, Phase I Kabul-Kandahar Highway,” 14 December 2003, http://www.usaid.gov/press/factsheets/2003/fs031214.html.

Andrew S. Natsios (Lieutenant Colonel, USAR Ret.) is Administrator of the US Agency for International Development (USAID). President Bush also has appointed him Special Coordinator for International Disaster Assistance and Special Humanitarian Coordinator for the Sudan. Natsios served previously at USAID as director of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance from 1989 to 1991, and then as assistant administrator for the Bureau for Food and Humanitarian Assistance from 1991 to 1993. He is the author of U.S. Foreign Policy and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (CSIS, 1997), and The Great North Korean Famine (US Institute of Peace, 2001). He retired from the US Army Reserve in 1995 after 23 years of service, and he is a veteran of the Gulf War.

Technical assistance requested by president Ertha Pascale Trouillot in 1989 to support the elections

Request for an economic embargo against

Haiti by Jean Bertrand Aristide in 1992

Aristide request for MICIVIH February 1993 – May 1998

U.S. Military intervention requested by Aristide in 1994

UNMIH September 1993 – June 1996

UNSMIH July 1996 – July 1997

UNTMIH August 1997 – November 1997

MIPONUH December 1997 – March 2000

MICAH March 2000 – Feb. 2001

Aristide request to the Clinton Administration for military intervention in 2000

Aristide request to the Bush Administration for military intervention January 2004

Aristide request to the United Nations in January 2004: MINUSTAH April 2004 – Présent

Aristide request to OAS 2000 – 2007

Aristide request to CARICOM 2001 – 2004

The United Nations in Haiti has spent millions of dollars over the past seventeen years deploying peace keeping missions -- with nothing to show for it (see The International Aid Debacle @ http://solutionshaiti.blogspot.com/2007/01/international-aid-debacle-how-to-get.html ). Clearly, their strategy has not been effective, or there would not be a continuing need for such intervention. One of the major reasons for this is: they are not really building capacity. Rather, they are doing the work themselves. They run elections for Haitians, conduct police operations themselves, openly promote the amendment of the Haitian constitution, and reform of the judicial system. This is a mistake. It goes against the old adage of “teaching a man to fish” and against the basic principles of nation building.

If MINUSTAH is to be successful in Haiti and leave behind strong and democratic institutions, they must revise their current strategy in the light of the Nine Principles of Development and Reconciliation written by Andrew Natsios. The United Nations and the Organizations of American States need to strengthen their working relations. The offices of the Secretaries General of the OAS and the UN should create an independent, non-partisan commission to conduct a quarterly evaluation of the performance of the missions, the Haitian government, and the perception of the Haitian people, civil society and political parties. Such commission could be comprised of former U.S, Canadian, Caribbean and European Government officials and Haitians living abroad with strong records of accomplishment of political development success. In this way, we could ensure an honest assessment of the current situation and allow for corrections in the mission plans before we continue to waste time and energy on ineffective tactics. Stanley Lucas------------------------------------------

The Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development -----

ANDREW S. NATSIOS

Autumn 2005

The US foreign assistance community is in the midst of the most fundamental shift in policy since the inception of the Marshall Plan at the end of World War II. The events of 11 September 2001 suddenly and unexpectedly forced the United States to confront a historic challenge equal in magnitude to the Soviet threat of the Cold War. The tragedy initiated a series of changes leading to the most extensive government reorganization since the Truman Administration created the National Security Council and the Department of Defense. No agency has undergone a greater degree of internal review and transformation than the US Agency for International Development (USAID). For better or worse, USAID is on the front lines of the dominating news stories of the day, whether engaging in reconstruction work in Afghanistan or providing tsunami relief in South Asia. This renewed prominence is not an accident. On the contrary, President George W. Bush’s Administration has made development work a national security priority; the September 2002 National Security Strategy underscores development as one of three strategic areas of emphasis (along with diplomacy and defense), and clearly states that “including all of the world’s poor in an expanding circle of development—and opportunity—is a moral imperative and one of the top priorities of US international policy.”1

This new development climate has brought about internal recognition in the agency that it requires a more uniform and consistent set of guiding principles, and that these principles must accurately reflect how USAID approaches development from all levels—from day-to-day project operations to high-level policy decisions. Drawing on more than 40 years of institutional development experience and building on a series of recent policy strategies,

including U.S. Foreign Aid: Meeting the Challenges of the Twenty-first Century and the Fragile States Strategy,2 this article presents the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development, comprising ownership, capacity building, sustainability, selectivity, assessment, results, partnership, flexibility, and accountability.

The purpose of this article is to introduce and analyze the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development to the military community. In a time of increasing collaboration between the two organizations, it is important that the military gain a better understanding of how USAID and development agencies generally approach their work, and how the two communities can beneficially build on this cooperation. This article specifically incorporates project-level examples from Afghanistan to better illustrate and provide context for the Nine Principles. Afghanistan is not presented as an ideal development context in which to apply the principles, but it demonstrates how they may apply even in fragile, less-stable environments. Ultimately, the article contends that the Nine Principles are integral to reconstruction and development success. When a foreign assistance agency adheres to the Nine Principles, this greatly enhances the likelihood of success. Conversely, failure to take the Nine Principles into account when designing and managing a program increases the risk of program failure.

Just as a particularly skilled battlefield commander can violate one or two of the principles of war and still prevail, a development officer may violate one or two of the development principles and still succeed. But generally development agencies ignore these principles at great risk, particularly in countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Sudan, where major reconstruction efforts are under way. ---------------------------------------------------------------

Background

There are a number of different ways to approach international development. USAID’s White Paper on Foreign Aid enumerates five core development goals: promote transformational development, strengthen fragile

states, provide humanitarian relief, support US geostrategic interests, and mitigate global and transnational problems.3 Overall, USAID is the leading US government agency responsible for promoting peace and stability by fostering economic growth, protecting human health, providing emergency humanitarian assistance, increasing literacy, and enhancing democracy in developing countries.

The origins of USAID and the modern US development discipline can be traced to the end of World War II. Top policymakers of that era realized that traditional American isolationism was no longer a tenable strategy and argued for a new approach. The cornerstone for this policy shift occurred on 5 June 1947, when Secretary of State George C. Marshall gave a commencement address at Harvard University and advocated that the United States use its power and wealth to nurse a world devastated by war back to “economic health.”4 This speech gave rise to the Marshall Plan and formed the historical foundation for USAID (the agency was officially established in 1961 by executive order of President John F. Kennedy, combining three existing agencies).

The evolution of US foreign assistance policy is now in its most critical stage since the Marshall Plan. The strategic goals outlined in the National Security Strategy confirm that a new development paradigm has emerged: USAID no longer operates on the periphery of US foreign policy. Instead, there is a broadening recognition that the agency and development work in general are vital to US national security interests.

One implication of elevating development work as one of the three pillars of national security is increased collaboration between the military and development communities. Situations like Afghanistan and Iraq—which require a broad-based, coordinated humanitarian response—are becoming increasingly common. More significantly, the success of military strategy and the success of development policy have become mutually reinforcing. Development cannot effectively take place without the security that armed force provides. And security cannot ultimately occur until local populations view the promise of development as an alternative to violence. Moreover, while the military is well placed to undertake certain types of stabilization projects, civilian agencies can relieve the military of many reconstruction and development projects which it is not well suited to oversee. Thus, it is important that the military gains a clearer understanding not only of how USAID implements a project or operates a field mission, but a deeper grasp of the core principles the agency follows when approaching all development work.

At a basic, theoretical level, the Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development are inspired by the Nine Principles of War, which are inscribed in modern Army field manuals.5 In the past decade, the military has attempted to forge a closer theoretical link between post-conflict development work and military interventions. In the mid-1990s, it established the six principles of Military Operations Other Than War (MOOTW), which served as an initial bridge between the two disciplines. More recently, especially since 9/11, there has been a growing recognition that conflict should be defined in more fluid terms; that the line between formal military engagement and informal insurgencies is increasingly blurred. As a result, military thinking has evolved and now incorporates the phrase “stability operations” as a term of art to describe post-conflict nation-building efforts.6 Despite this shift, the military continues to use the Nine Principles of War as an intellectual basis for all military operations, including stability operations (it has folded the six principles of MOOTW into the Nine Principles of War rubric). The Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development have evolved from a similar institutional experience. They distill fundamental lessons from this experience and bring greater clarity to the operative principles that inform the mission of USAID. --------------------------------

Principle 1: Ownership

Build on the leadership, participation, and commitment of a country and its people.

The first principle of development and perhaps the most important is ownership. It holds that a country must drive its own development needs and priorities. The role of donor organizations is to support and assist this process as partners toward a common objective.7 It is essential that the country’s people view development as belonging to them and not to the donor community; development initiatives must meet the country’s needs and its people’s problems as they perceive them, not as distant policymakers imagine them. Nurturing country ownership is a laborious process that emerges with time and effort. It requires a strong agency ground presence in order to build credibility, trust, and consensus in the local population.

What the people of a community want ultimately counts a great deal, since their community belongs to them and not to external aid agencies. When ownership exists and a community invests itself in a project, the citizens will defend, maintain, and expand the project well after donors have departed. If what is left behind makes no sense to them, does not meet their needs, or does not belong to them, they will abandon it as soon as aid agencies leave. It does take much longer to engage national and local leaders patiently in their own development than to simply impose it from the outside quickly and autocratically, but the result makes all the difference.

US policy in Afghanistan has emphasized the ownership principle and has focused on encouraging Afghans to take government leadership positions. The selection of Hamid Karzai as President of Afghanistan is a good

illustration. In December 2001, the four major Afghan factions met in Bonn, Germany, to select an interim leader. They subsequently chose Karzai to head the Afghan Transitional Authority. What is significant about this model is that Karzai is Afghan and his ministers are all Afghan-born as well.8 Karzai has additionally strived for ethnic balance; the interim cabinet comprehensively represented all the various political groups in Afghanistan, from Mujahiddin and Northern Alliance factions to European and American members of the Afghan Diaspora.9

It is important to have a national lead the country and to have nationals head the ministries for several reasons. First, selecting a national as head of state provides a much greater degree of legitimacy; the Afghan community will inherently trust and relate better to an Afghan leader than to an outsider running the country. Second, having an Afghan leader eliminates the language barrier. Documents and meetings do not have to be translated, and general communication is facilitated. Third, it is vital that Afghans run the government transition process themselves; this may be more chaotic in the short-term, but it also means that Afghans will own the process and ultimately be responsible for the choices they make. Fourth, an Afghan such as Karzai understands the nuances of the political situation better than any outsider and is more capable of navigating through problems as they arise. Finally, when attempting to win the “hearts and minds” of the local population, especially in the midst of Taliban and warlord turmoil, it is essential to mobilize the Afghan people behind the government’s policy. One of the most important factors responsible for the growing stability and prosperity of Afghanistan is this successful mobilization of the great bulk of the population behind national government policies. This is best accomplished by an Afghan leader. ---------------------------------------

Principle 2: Capacity Building

Strengthen local institutions, transfer technical skills, and promote appropriate policies.

Capacity building involves the transfer of technical knowledge and skills to individuals and institutions so that they acquire the long-term ability to establish effective policies and deliver competent public services. One of its most important by-products is that the country increases its ability to retain, absorb, and facilitate economic investment, whether from donor assistance or from private sources of Foreign Direct Investment. Ultimately, an improved governance and investment environment is a necessary condition for sustained economic growth in any country.

The development community recognizes that the right government policies underscore all successful development efforts. Simply put, a country

with weak governance institutions and misguided policies will have a limited ability to lead its own economic and social development. For example, it is not enough to build universities and educate a country’s population. This effort must be accompanied by direct opportunities that will allow university graduates to become future political and business leaders.

Capacity building applies in the military context as well. For example, in Afghanistan the US military has established the Kabul Military Training Center as part of a $750 million plan to prepare and train a national force “capable of replacing the militias” that drove out the Taliban in 2001.10 The expectation is that the US military will transfer necessary technical skills to the Afghan National Army (ANA), which will gradually assume full responsibility for the country’s security needs.

Among the most important capacity building activities that USAID implements in Afghanistan are education programs; these are the building blocks that will foster the next generation of Afghan doctors, lawyers, engineers, and technocrats. Capacity building has occurred in several different forms. On one level, USAID has directly improved the performance and functioning of the Ministry of Education by providing technical and management advisers, assisting with curriculum development workshops, and ensuring that the ministry can manage textbook printing requirements in future years.11 On another level, USAID has built individual teacher capacity through programs such as the radio-based teacher training (RTT) program, which targets teachers who reside in remote areas of the country. As of June 2005, some 65,000 teachers have been trained through broadcasts that strengthen their teaching skills and spread civic and educational messages. About 7,500 more teachers have been trained through face-to-face instruction, and 6,800 in an accelerated training program.12 As more teachers have been trained, more children have returned to school: primary school enrollment has increased from a pre-war total of one million (2001) to 4.8 million as of December 2004.13

The development community accepts the notion that strong human and technical capacity are necessary prerequisites for stability and economic growth. Simply put, a country with weak government institutions staffed by unqualified and inefficient officials will have a limited ability to lead and sustain its own economic and social development. ------------------------------

Principle 3: Sustainability

Design programs to ensure their impact endures.

The core of the sustainability principle is that development agencies should design programs so that their impact endures beyond the end of the project. Sustainability also encompasses the notion that a country’s resources are

finite and development should ensure a balance between economic development, social development, and democracy and governance. The sustainability principle forces aid managers to consider whether the technology, institution, or service they are introducing to a society will have a lasting effect.

Sustainability is equally applicable in the military context. In order for the military to accomplish its missions, commanders must persevere; they must balance the need to quickly execute their immediate mission and then depart, on the one hand, with the necessity of developing sustainable local police and military forces capable of protecting the country in the future against resurgent Taliban or al Qaeda forces, on the other.14 For example, it is not enough for the US military to train and initially equip ANA soldiers. The best-trained army will languish and deteriorate without ongoing government support and funding. Sustainability demands that the Afghan government eventually start replacing external military assistance with domestic tax revenues to fund the Afghan National Army and other public services.

Sustainability is especially important in times of turmoil; if proper sustainable structures are in place, then the project will endure despite surrounding conflict. A good case in point is the Kajaki Dam in Afghanistan. The dam was originally constructed in 1953 with funding from the US Export-Import Bank; it was upgraded with USAID assistance in 1975.15 It has supplied continuous electricity to the provinces of Helmand and Kandahar and consistently provided irrigation water to the surrounding valley. After the invasion of the Soviet army in 1979 and the subsequent withdrawal of US assistance to Afghanistan, the engineers in charge of its maintenance were able to keep the dam operational and productive through 23 years of civil war and Taliban oppression without any external assistance, supplies, or funding.16 The dam’s remarkable sustainability has been due to a combination of factors: extensive engineer training that emphasized dam maintenance, durable construction design, and adherence to the ownership principle—Afghans took responsibility for maintaining the dam themselves, and they did everything possible to keep it operational.

In contrast, other development efforts in Afghanistan have been less successful because they have failed to take the sustainability principle into consideration. For example, one outside agency intended to provide electricity to a remote village. Rather than extend power lines from a central grid, they supplied a diesel generator. In the short-term, the village had an ample source of electricity. In the long-term, this proved unsustainable as the village had no means or resources to replenish the spent fuel and lacked the technical ability to repair the generator as required. Sustainability means ensuring that the program’s impact will endure. It entails, for instance, making certain that a nearby aquifer can adequately support the local population’s long-term water needs before tapping the source and constructing a water system.

Ownership, capacity building, and sustainability form an iron triad of principles underscoring all successful and enduring development and reconstruction projects. These principles cannot be applied successfully over short time periods. They require years of consistent effort and support or they will fail. There are no quick fixes in successful development. A development officer ignores these principles at great risk: alienation of the local population and failed projects. ----------

Principle 4: Selectivity

Allocate resources based on need, local commitment, and foreign policy interests.

The selectivity principle directs US bilateral assistance organizations to invest scarce aid resources based on three notions: humanitarian need, the foreign policy interests of the United States, and the commitment of a country and its leadership to reform. To maximize effectiveness, donor resource allocation must be targeted where it can have an appreciable impact and where the recipient community demonstrates commitment to development goals.

In military terms, selectivity closely relates to the principle of “mass”—concentrate military power at the decisive place and time. The underlying notion is that resources are finite and are most effective when concentrated together in select situations. Any allocation of resources, whether in combat operations or infrastructure projects, must take into consideration foreign policy interests, political circumstances, and ground-level need.

President Bush’s Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) exemplifies the principle of selectivity. The MCC is not meant to provide everlasting across-the-board economic growth assistance. Instead, it focuses on transformational development, fostering far-reaching, fundamental changes so that further economic and social progress can be sustained without dependence on foreign aid. Thus, the MCC applies to a specific country archetype: one that possesses a strong governance framework and which requires large-scale capital investment as a final ingredient toward full-scale development and growth. To determine which countries fit this transformational development model, MCC rates countries on a 16-point scale in the broad categories of ruling justly, investment in people, and economic freedom. It then selects countries eligible for funding based on a country’s rating.

In Afghanistan, the restored Kabul-to-Kandahar highway illustrates the selectivity principle.17 More than 35 percent of the country’s population lives within 50 kilometers of this highway; unfortunately, over two decades of war and poor maintenance had devastated the road.18 Restoration of the highway was a high priority for President Karzai and President Bush: USAID was asked to implement the project over a short time frame of 14 months. The project was crucial to extending the influence of the new government; the road has led to increased rates of economic development, it has fostered civil society, and it helps ensure unity and long-term security in the country.19 In addition, the road circulates through a significant number of Taliban strongholds, so upgrading the road has diminished the Taliban’s ability to exert influence in this portion of the country.

The highway is a primary example of the selectivity principle. USAID factored in the developmental need the highway would serve (access to markets and cities), the foreign policy interests of the United States (promote economic development and country unity, counteract Taliban influence), and the commitment of a country and its leadership to reform (President Karzai is an acknowledged reformer with exceptional commitment to the project). ------------

Principle 5: Assessment

Conduct careful research, adapt best practices, and design for local conditions.