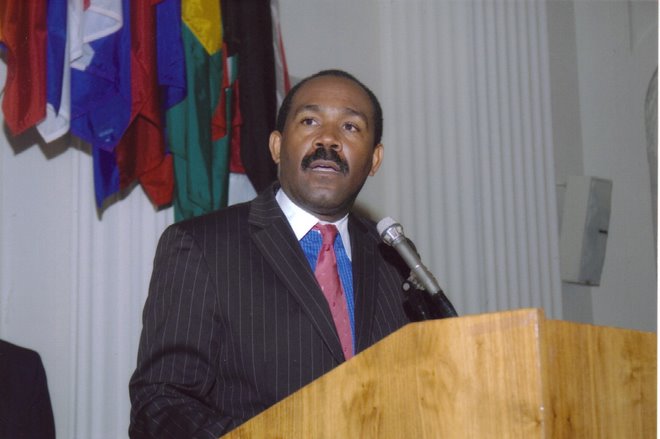

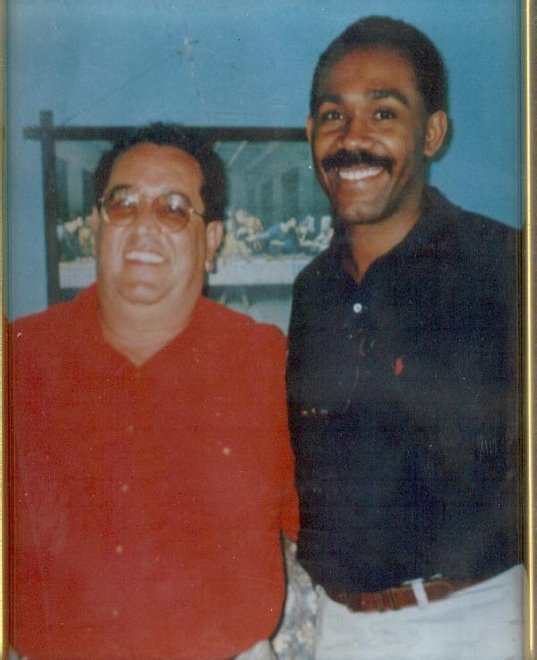

Photo de Jean Bertrand

Aristide a la Maison Blanche quand il demandait officiellement l'occupation d'Haïti

en 1994.

Ce 15 Octobre 2013 ramène le dix-neuvième

anniversaire de l’occupation militaire des Etats Unis en Haïti sollicite par le

Président Jean Bertrand Aristide en 1994. Le peuple Haïtien attend toujours des excuses de Jean Bertrand Aristide. C’est le moment de rappeler pour les générations

futures que cette demande officielle d’occupation militaire d’Aristide était un

acte de trahison parce qu’elle viole la constitution d’Haïti. Aristide par cette décision mettait

aussi en veilleuse de la souveraineté nationale d’Haïti si chèrement acquise

par les pères de l’indépendance. Nous ne devons pas non plus oublier qu’après

la demande d’intervention militaire de Jean Bertrand Aristide alors que les

bateaux, avions, engins militaires et la machine de guerre des Etats Unis étaient

déjà en route pour bombarder Haïti, n’était-ce l’action diplomatique de dernière

minute de l’ancien Président Jimmy Carter, du General Colin Powell et du Sénateur

Sam Nunn des milliers de citoyens haïtiens auraient pu perdre la vie et vivre

les moments inoubliables de la guerre avec les bombardements, la mitraille et

autres psychoses que cela laisse sur tout un peuple. Grace a leur intervention,

l’invasion brutale sollicitée par Aristide l’homme des occupants qui n’avait

pas hésite a donner le feu vert a pu être évitée. Bay kou bliye pote mak sonje! Se pa yon ti dezod tankou Aristide te

dil, se te yon gwo trayizon!

Dessalines pat nan achte figi

De la demande officielle d'embargo contre Haïti

en 1992, en passant par la demande officielle d'intervention militaire en Haïti

en 1994 ou encore l'invitation officielle des troupes militaires de l'Afrique

du Sud le 1 Janvier 2004 aux Gonaïves pendant que nous étions en train de

célébrer nos 200 ans d’indépendance, voir: http://metropolehaiti.com/metropole/archive.php?action=full&keyword=mbeki+aux+gonaives&sid=0&critere=0&id=7742&p=1

et sa dernière demande officielle pour l'envoi de 3000 soldats américains en Haïti

en Février 2004, l'ancien Jean Bertrand Aristide a viole la constitution de

1987, trahi sa patrie et vendu la souveraineté nationale d’Haïti. Les demandes

d'interventions militaires sollicitées officiellement par un Président de la république

d'Haïti sont condamnées par la constitution de notre pays qui considèrent ces

actions comme un acte de haute trahison. Dix neuf ans après Jean Bertrand

Aristide et Fanmi Lavalas n’ont toujours pas présente des excuses au peuple Haïtien

pour ses demandes répétées d’occupations qui ont hypothèque la souveraineté

nationale de notre pays.

Aristide devant le Pentagon recevant les honneurs militaires apres avoir sollicite l'occupation d'Haiti

L’histoire de l’occupation récente de la république

d’Haïti par des troupes étrangères a commence en 1992. Le Président

constitutionnel Jean Bertrand Aristide victime d’un coup d’état illégal le 30

Septembre 1991 partira en exil. Une fois a l’étranger, dans le cadre de son

plan pour la reconquête du pouvoir politique, Jean Bertrand Aristide, prendra unilatéralement,

sans consultation avec le parlement haïtien et les forces démocratiques d’Haïti

un ensemble de décisions qui ruineront l’économie d’Haïti avec des impacts

sociaux déplorables appauvrissant

tout une population tout en vendant la souveraineté nationale.

Pour commencer, Jean Bertrand Aristide pour

retourner au pouvoir décida d’imposer en 1992 un embargo économique sur Haïti

en lieu et place de sanctions ciblées contre les responsables du coup d’état.

Les résultats de ces sanctions imposées par Aristide avec le support de ces

allies de la communauté internationale seront catastrophiques pour Haïti et son

peuple. Les plus démunis et les classes moyennes ont été les plus grandes

victimes de l’horreur dénommé embargo impose par Aristide. Comment un Président

d’Haïti a-t-il pu commettre une telle ignominie ? L’embargo Aristide tuera

des milliers d’enfants selon une étude de l’UNICEF et de l’université américaine

Harvard. Il a eu un impact terrible sur les femmes, la sécurité alimentaire et

le système de santé causant la malnutrition, le manque de médicaments dans les

centres de sante et l’accès aux soins de base.

Les vendeurs de notre patrie au Pentagon en 1994

L’embargo d’Aristide a fait perdre 300.000

emplois a Haïti et détruira l’environnement a cause de l’accélération du déboisement

du au blocage maritime militaires bloquant la plupart des importations inclut les

produits pétroliers. L’horreur économique de l’embargo avec ses conséquences

comme par exemple la famine causant la malnutrition générale, poussa les citoyens à quitter le pays a

la recherche d’opportunités pour faire vivre leur famille. Malgré les horreurs économiques

et sociaux de l’embargo qui frappaient les enfants, les jeunes, les femmes, les

hommes et les vieillards, Aristide déshumanise continuait a scander a la radio

qu’il fallait augmenter les sanctions. Les copies audio de ces déclarations

sont encore disponibles dans toutes les stations de radios d’Haïti et de la

diaspora malgré les efforts et les gros moyens déployés par Aristide pour faire

disparaitre la documentation audio, vidéo et écrite de ses crimes contre son

peuple.

Gade yo kap siyen...

Jean Bertrand Aristide demanda officiellement

aux Etats Unis de le restaurer au pouvoir avec 20.000 soldats et l’Agence Américaine

d’Intelligence (CIA). La stratégie d’Aristide pour reprendre le pouvoir

comprendra deux axes. L’axe interne et l’autre externe. Au niveau interne:

1.

Fabriquer et projeter devant l’opinion publique et la communauté

internationale des violations massives de droits humains. C’est vrai que les militaires et l’organisation paramilitaire FRAPH étaient

responsables de nombreux violations de droits humains pendant la période du

coup d’état mais c’est aussi vrai qu’avec son réseau Jean Bertrand Aristide

faisait voler a travers les morgues des hôpitaux du pays des cadavres de

citoyens morts naturellement pour les cribler de balles pour ensuite les déposer dans les rues d’Haïti

pour gonfler le dossier des droits humains.

2.

Utilisation de ses réseaux politiques pour distribuer de l’argent pour

construire des bateaux et provoquer un flot massif de boat people vers Miami. Dans le cadre de la préparation

de ce scenario boat people le teledjol Haïtien avait identifie a l’époque le

Maire Lavalas de la commune de Delmas comme celui qui avait distribue l’argent

pour construire les bateaux qui allaient transporter des milliers de citoyens haïtiens

des milieux ruraux d’Haïti vers Miami. Il n’attendait que le signal donne de Jean

Bertrand Aristide qui était à Washington travaillant activement en ce sens. Le

milliers de gens en mer qu’on verra plus tard sur CNN plus tard était le coup

boat people organise et prépare par Aristide pour forcer Clinton a intervenir

en Haïti sur sa requête.

Au niveau externe:

1.

Employer des lobbyistes pour préparer et gonfler l’opinion publique

pour une intervention militaire. Tout un réseau de

lobbyistes avait été employé par Aristide avec les 80 millions de dollars de la

teleco qui étaient dans les banques américaines. Michael Barnes le chef de la campagne de Bill Clinton dans le

Maryland était parmi les employés ainsi que de nombreux proches du Concrétionna

Black Caucus incluent Randal Robinson et sa femme Hazel étaient sur le payroll.

Ils deviendront tous millionnaires sur le dos du peuple haïtien. Les 80

millions de la teleco d’Haïti se sont envoles dans les poches de ces messieurs

et ceux d’Aristide. Leur rôle était de pousser l’administration américaine vers

l’intervention militaire a travers des articles de journaux, la grève de faim

de Randal Robinson devant la Maison Blanche tout en plaçant des éléments clefs

et favorables dans des positions stratégiques a l’intérieur de l’administration

Clinton. Ces influences leur permit de faire revoquer l’Ambassadeur Lawrence

Pezzulo et le remplacer par un proche de Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) et

Aristide, William H. Gray. Le

livre non publie de Pezzullo “The Leap into Haïti: Or How Not to Conduct U.S.

Foreign Policy in the Post Cold War” offre des détails intéressants sur comment

Aristide a planifie, sollicite et obtenu l’intervention militaire des Etats

Unis pour le restaurer au pouvoir en Haïti.

2.

Utilisation les missions diplomatiques d’Haïti a Washington, Nations

Unies, OEA et la CARICOM pour faire avancer le dossier de l’intervention

militaire. En plus de la demande formelle d’occupation

militaire de Jean Bertrand Aristide, il utilisera les missions diplomatiques

pour les requêtes formelles dans les institutions multilatérales et rapports bilatéraux.

Quatre missions diplomatiques d’Haïti ont joue un rôle clef dans l’agenda de la

demande d’occupation voulu par Aristide: Washington, l’OEA, les Nations Unies

et la CARICOM. En plus la mission de Washington jouait un rôle additionnelle

pour faciliter l’occupation: payer des journalistes américains charges de

publier des histoires préparées par Aristide et les lobbyistes qui

travaillaient le Congres et l’Administration pour faire avancer le dossier de

l’intervention.

3.

Demander officiellement l’intervention militaire aux autorités américaines

pour le restaurer au pouvoir demanda officiellement au pouvoir en Haïti. Prière de consulter la vidéo d'Aristide remerciant au Pentagone le

Ministre américain de la Défense William Perry et le General Shalikasvili,

cliquez ici: http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/60373-1

Aujourd’hui il y a dix neuf ans Aristide

sollicitait officiellement de la Maison Blanche et du Pentagone une

intervention militaire en Haïti pour le restaurer au pouvoir en Haïti. Aristide,

en prenant la décision de faire envahir Haïti en Septembre 1994, par des

militaires étrangers n'avait consulte que ces conseillers proches Casimir,

Longchamp, Woerleigh qui etaient avec lui aux Etats Unis. Dans sa campagne de

sollicitation officielle de l'occupation de la république d'Haïti, Aristide mit

catégoriquement de cote les sénateurs et députes la 45e législature et les forces

politiques du pays. Il mit aussi de cote ses allies politiques en Haïti opposes

a sa demande d'occupation. A l'époque Gérard Pierre Charles de l'Organisation

du Peuple en Lutte (OPL), Jean Marie Vincent et d'autres membres du mouvement

lavalas qui constituaient le front interne contre le coup d'état militaire étaient

contre l'intervention militaire étrangère en Haïti. Les membres du front interne lavalas de résistance

combattant le coup d'état pensaient pouvoir réinstaller l'ordre démocratique en

Haïti sans occupation militaire étrangère. Aristide voulant l'intervention

militaire des étrangers pour revenir au pouvoir était en conflit avec ce groupe

de lavalassiens de l'intérieur oppose a l'occupation. Cette différence causa

l'assassinat de Jean Marie Vincent selon les analystes qui attribuèrent le

meurtre à Aristide.

Jean Bertrand Aristide le demandeur officiel

de l'occupation militaire du 15 Octobre 1994 sera-t-il encore silencieux ce 15

Octobre 2013 ou finalement demandera-t-il pardon à la nation?

C'est aussi Jean Bertrand Aristide qui

introduira les soldats de l'ONU en Haïti, il remplacera les militaires américains

par les militaires des Nations Unies en 1995. A cause de la politique interne, les autorités américaines décidèrent

de rapatrier leur troupe en Haïti. Pour les remplacer Jean Bertrand Aristide

fit une demande de soldats étrangers à l’ONU qui accepta. Cette première

mission militaire dut déployée en Haïti, à l'époque elle portait le nom de MINUHA.

De 1994 a 2004 Aristide a sollicite

officiellement douze demandes d'occupations. En 2006 René Préval, Jacques

Edouard Alexis continueront cette politique de renouvellement de l'occupation. De

2006 a 2011 ces responsables de l'état n'ont jamais présente à la nation le

plan de reconquête de la souveraineté nationale d'Haïti a travers le

renforcement et la reconstruction de nos institutions de sécurité. La mise en

place d'une stratégie de sécurité nationale ne fait pas partie de leurs

priorités. Apres Lavalas ce sont le CPP, l'INITE et Louvri Barye qui choisirent

l'occupation.

Aristide débarqua a Port-au-Prince le 15

Octobre 1994 dans un avion américain, puis fut déverse au palais national par

un hélicoptère de la marine américaine. Aristide était fier de sa performance,

il racontait à ses conseillers proches comment il a roule Bill Clinton.

Sachant qu'il avait viole la constitution en

sollicitant et provoquant cette intervention militaire, Aristide déclara plus

tard dans un discours a la population que "li fe yon ti dezod".

Randall Robinson fut récompense par Aristide a

travers les millions que recevra plus tard sa femme Hazel Robinson de l'état Haïtien

a travers des contrats de lobbyistes. Pour les détails cliquez ici: http://www.haitipolicy.org/Lobbying7.htm

Le livre de Robinson devait

servir pour la réalisation d'un film pro Aristide sur l'histoire d'Haïti.

Depuis honteux et maltraites par des historiens

Haïtiens pour ses choix d'occupations Aristide utilise des faux noms et

quelques proches a son service sur l'internet, l'un deux, Joël Léon, pour

promouvoir une propagande qui vise a changer l'histoire des demandes

officielles d'occupations d'Haïti faites par lui.

Aristide sera-t-il silencieux ce 15 Octobre

2013? Je suis certain qu'il le restera encore cette année.

Concernant la demande d'occupation de 1994 les

journalistes Haïtiens devront demander a Titid , l'homme des occupants,

pourquoi ne pouvait-il pas avoir le comportement noble du président Manuel Zelaya du Honduras qui est

rentre chez lui sans solliciter un soldat étranger après le coup d'état militaire

contre lui? Il faudra aussi demander au Lavalas et a LESPWA-INITE qui etaient

au pouvoir depuis vingt ans pourquoi Haïti comme l'Irak n'a-t-elle pas son plan

de reconquete de la souverainete nationale pour le retrait progressif des

troupes etrangeres? Est-ce que

c’est parce qu’ils eaient les hommes de l’occupant qu’ils n’ont pas pu parler

de la reconquete de la souverainete nationale?

Quand a Michel Martelly il a propose le 18

Novembre 2011 un plan de reconquete de la souverainete nationale qui passe par

la professionalisation de la police, la construction d’une armee professionnelle

et le retrait organise de la MINUSTAH. Mais ce sont les memes arnacho

populistes lavalassien Moise Jean Charles, Simon Desras qui ont fait du

lobbyong a Washington pour dire qu’Haïti n’avait pas besoin d’une armee.

Martelly a donc renouvele le mandat de la MINUSTAH.

Pour les etudiants qui choississent ce theme

pour leur these, un petit rappel des demandes recentes et officielles

d'occupations en Haïti.

Il y a eu beaucoup de debats autour de l'idee

de "l'occupation etrangere" en Haïti. les Haitiens, bien sur, sont

opposes a cette idee. Quelques

leaders Haitiens au pouvoir pour leur capital politique ont essaye de manipuler

les faits pour ne pas assumer la responsabilite d'avoir demande officiellement

l'intervention militaire des etrangers en Haïti. Les faits sont que de 1990 a

nos jours quatrorze missions etrangeres de formes variees ont ete deployer en Haïti,

a chaque fois, a partir d'une requete officielle du Gouvernement Haitien en

fonction. Les documents officiels sont disponibles pour prouver que ces

requetes ont effectivement ete faites. Voici la liste:

Assistance technique des Nations Unies

sollicitee par le president Ertha Pascale Trouillot en 1989 pour supporter l'organisation des elections elections

de 1990

Demande de l'imposition d'un embargo

economique des Nations Unies sur Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean

Bertrand Aristide en 1991

Demande de l'envoi d'une mission des Nations

Unies,MICIVIH, en Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean Bertrand Aristide

Fevrier 1993 a Mai 1998

Demande d'intervention militaire des Etats

Unis en Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean Bertrand Aristide en Septembre

1994

Requete d'une mission militaire des Nations

Unies,UNMIH, en Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean Bertrand Aristide

Septembre 1993 qui a termine sa mission en Juin 1996

Requete d'une mission militaire des Nations

Unies en Haïti, UNSMIH, sollicitee par le president Rene PrevalJuillet 1996 a

Juillet 1997

Requete d'une mission militaire des nations

Unies en Haiti,UNSMIH, sollicitee par le president Rene PrevalUNTMIH Aout 1997

a Novembre 1997

Requete d'une mission militaire des Nations

Unies en Haiti,UNSMIH, sollicitee par le president Rene PrevalMIPONUH Decembre

1997 a Mars 2000

Requete d'une mission militaire des Nations

Unies en Haiti,UNSMIH, sollicitee par le president Rene PrevalMICAH, Mars 2000

a Fevrier. 2001

Requete d'intervention d'Aristide a

l'administration Clinton, les huit points, sollicitee par Jean Bertrand

Novembre 2000

Requete d'une mission militaire des Etats Unis

en Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean-Bertrand Aristide Janvier 2004

Requete d'une mission militaire des Nations

Unies en Haïti sollicitee par le president Jean Bertrand Aristide Janvier 2004

MINUSTAH April 2004 a nos jours ;

Aristide a aussi sollicite l'intervention de

l'OEA 2000 a 2007 , toujours en Haïti

Aristide a sollicite l'intervention de la

CARICOM 2001 a 2004

Michel Martelly renouvelle le mandat de la

MINUSTAH 2012-14

-3.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)