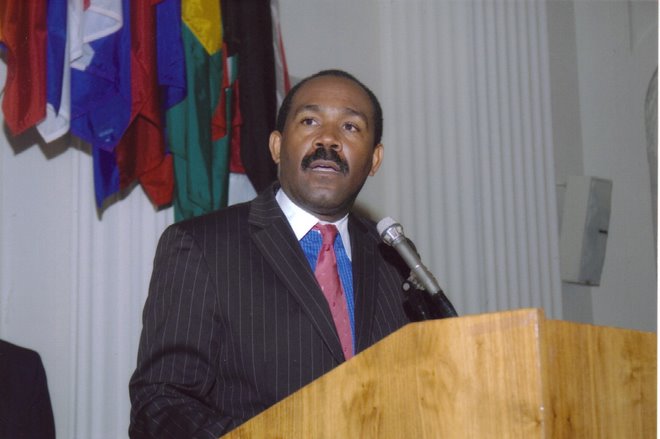

A. Duclona J.B. Aristide J.P. Lauture J.A.Nazaire

Ten years ago, a Haitian businessman named Claude Bernard Lauture, 51, and known as “Billy” was kidnapped and murdered. This week the Court of Assise in Paris convicted Amaral Duclona, a Haitian national, of the murder and sentenced him to 25 years in jail. If it weren’t for a Radio Vision 2000 interview with his widow, Marie Louise Michele Lauture, this conviction would have gone unnoticed. But on May 26, Marie Louise shared with the Haitian public her suffering and what she went though for the past ten years. This was one of the most emotional interviews I have heard and was shocking for all listeners that day. In it, she stated that former President Jean Bertrand Aristide was behind the murder, and she laid out his criminal mindset and the weaknesses of Haiti’s judicial system.

Bernard and Marie Louise Michele Lauture had five children over the course of a happy marriage. He was a reliable and respected Haitian businessman in the electrical engineering field. In 2003-04, the normally quiet couple took to the streets to peacefully protest against the growing repression and corruption in the Lavalas government led by Jean Bertrand Aristide.

By way of background, on November 26, 2000 Aristide put in

place a puppet electoral body to steal the election. News reports and Aristide supporters announced that he won a

whopping 83% of the vote, but neglect to mention that voter turnout was about

1% and ballot boxes were stuffed.

Then President Bill Clinton and National Security

Anthony

Lake Lake legitimized

the electoral coup by signing an eight-point agreement with Aristide, who

conceded to implement a variety of democratic measure and promote the rule of

law. At that time President Clinton had so much invested in his

foreign policy to Haiti given the 1994 military intervention that he had

limited options to deal with the Aristide electoral coup. Aristide knew it and tried to blackmail

the President.

When Aristide took office, instead of implementing the agreement

intended to bring return constitutional order to the country, he turned to his normal

violent political tactics ignoring the offers for political dialogue and

compromise made by the democratic opposition who were pressing the eight-point

agreement. Instead, he burned opposition

party headquarters and the private residences of the opposition leadership;

attacked women and youth organizations pressing for change; terrorized the

press and human rights activists.

Many people died facing his wrath.

When it was clear that Aristide would not compromise, the

Haitian citizens, with a proud tradition of holding their leaders accountable

and standing up for democracy, rallied to demand Aristide’s resignation including

members of his own coalition. Again, Aristide decided that repression, kidnappings and

killings were the best way to counter these peaceful protests. He organized

gangs and distributed machine guns and hand guns to the chimeres. These gang members, the chimeres, were

protected by a highly politicized police force that served Lavalas political

goals. Moise Jean Charles, a

member of his Lavalas coalition and a sitting Senator, decided to counter Aristide’s

violence by calling for the support of one of a former police commissioners,

Guy Philippe, according to two Lavalas

senators.

It was in this context that Bernard’s kidnapping was

organized and carried out. During

the interview

with Marie Louise Michele, she gave a detailed account of how Amaral Duclona --

under the instruction of Aristide -- kidnapped and killed her husband. She also shared details on how the

police investigation and judicial proceeding led to the facts. According to the interview and various

documents of the police and judicial proceedings, a member of Bernard’s family,

Mrs. Gladys Lauture, who was a close associate of Aristide, first approached

Bernard. Given his respected

position in the community and growing stance against Aristide, he was offered

various positions in the Lavalas cabinet, including Minister of Public Works

and Infrastructure, in exchange for his support. He declined.

Paraphrasing The Godfather, Gladys

informed him that this was not an offer you can refuse. Gladys’ son, Jean Paul Lauture, a

student at MIT, and an associate of Aristide also warned Bernard saying that

protesting against the President would not turn out well for him. Bernard remained firm in his rejection.

Gladys changed tactics and showed up at his house one day with a letter signed

by the President appointing Bernard as a board member for the state owned

electric company. Bernard was upset by this action, and said he was not for

sale. He again rejected the offer.

His wife admitted she counseled

him to accept the position so as to not annoy President Aristide. She suggested that he could resign

after two meetings claiming that the position was interfering with his ability

to manage his business and attend to family priorities. He followed her advice.

On January 6, 2004, Amaral Duclona, the head of one of

Aristide’s gangs, kidnapped Bernard while he was on his way to pick up his kids

at school. Right before the

kidnapping, Bernard was on the phone with his wife. At the end of the conversation they told each other “I love you” as was their custom. They

did not know that would be their last words or their last declaration of love. Shortly thereafter, the kidnappers

called the family and put Bernard on the phone with instruction on what to say.

The family could hear a voice in

the background telling him to request US$100,000. During that phone call, Bernard led the family to believe

that he was in the Canapé Vert Commissariat. The family contacted Gladys and pleaded with her to intervene

due to her relationship with Aristide. Meanwhile, Marie Louise Michele requested support from the

French ambassador to Haiti given Bernard’s dual citizenship.

During the trial, it came out that there was another kidnap

victim in the cell with Bernard who managed to be freed. According to the victim testimony, Amaral

Duclona and Junior Charles, alias Yoyo Piman, a lieutenant of Amaral, were

throwing Aristide pictures in Bernard’s face.

The link between Aristide, Amaral Duclona and Yoyo Piman was

Jacques Anthony Nazaire, who was officially in charge of Aristide’s garage and

car fleet, but was most known for managing the Aristide gangs.

Gladys Lauture told Michele Louise that she would see

Aristide on her husband’s behalf. Gladys

contacted Aristide the same day and when she returned the following day she

told Marie Louis Michelle that she was leaving the country for a medical visit scheduled

months ago. She vanished.

The family had no option but to await another call with

instructions on where they should drop the money. That call never came. Instead, a heavily armed group of thugs went to the national

morgue and dropped off the dead body of Bernard Lauture with specific instructions

to the morgue guardian on where to place the corpse. That day, Aristide’s gang members, or chimeres, had control

of the streets in Port-au-Prince. They

destroyed several businesses and with blind and brutal violence went after

anyone who opposed them.

On January 8, the widow, Marie Louise Michele, went to the

morgue aided by a childhood friend. When she got there, a tearful morgue guardian asked her for

forgiveness and told her that he did not know that was her husband. He said that they give him specific

instructions to poorly manage the corpse. He retrieved Bernard’s dead body for her confirmation. She saw at least 10 bullet holes in his

lifeless body. She was forbidden

to take possession of his body at that point because according to Haitian law a

medical examiner must conduct an autopsy prior to releasing the body. She could not find the medical examiner.

When Marie Louise Michele was leaving the morgue, Jean Paul

Lauture, on behalf of Jean Bertrand Aristide, threatened her. He told her that the game she was

playing with the French embassy is not going to be good for you. Marie Louise Michele has not told anyone

of her discussions with the French government, and replied, “I don’t understand

what you are saying to me.” My

husband Billy is dead. I did not

even cry, when I saw him. I got on

my knees and prayed to God. I said

to God you gave him to me and now you took him back. That’s your will, God.” While she was saying those words, she heard Jean Paul on his

cell phone say, “Yes, Excellency”.

He then said, “You don’t with who I am talking? I am talking with

President Jean Bertrand Aristide.” Jean Paul said that the President asked me to convey a

message to you, Marie Louise Michele: “A dog with tale does not cross fire,”

which in creole means that you better be careful or your kids (the tale) are

next. This remark betrayed the

fact that Aristide was worried about the French embassy investigation.

Facing these threats from Aristide, Marie Louise Michele and

her five children fled Haiti to exile in Madrid. Before to her departure, aided by a Haitian human rights

organization, she filed her deposition on her husband’s murder with the Haitian

judicial system through the Office of Commissaire du Gouvernement. Aristide had

that office ransacked and her file disappeared.

While the Haitian judicial proceeding was essentially dead,

the French judicial system was still proceeding with an investigation. During the judicial proceedings in

France, Jean Paul Lauture was summoned by the court to testify. He declined saying that it would disrupt

his studies at MIT. Both Gladys

and Jean Paul escaped prosecution despite their full awareness of Aristide’s

intent to kidnap and murder Bernard and their role as intermediaries in

delivering specific threats against the family.

Marie Louise Michele believes that Gladys and Jean Paul were

merely functionaries and messengers.

Rather, she fully believes that despite the conviction of Duclona,

former President Aristide is the guilty party and evidence presented during the

trial, including phone records and witness testimony, supports that. The judicial proceedings established that

Amaral Duclona was responsible for Bernard Lauture’s killing, but Marie Louise

Michele believes that Jacques Anthony Nazaire and Aristide should have to face

a jury as well, but knows they never will. She deplores that the Haitian judicial system is weak and

witnesses in Haiti are still afraid of the perpetrators.

Quite unfortunately, she has a valid point and is not the

only family to face this tragedy. The judicial proceedings

for the assassination of the journalist Jean Dominique in 2000 are ongoing. Over the past 14 years, Aristide has had

witnesses killed and used political power to block justice. Four months ago, Judge Yvickel Dabrezil

concluded his findings and identified

the nine people responsible for Jean Dominique killing. All of them henchmen of former President

Aristide, who allegedly had him killed because Dominique represented a threat to

his return to power. The investigation into the murder of Venel Joseph, a

former governor of Haiti’s Central Bank, is facing similar political pressure. Venel was going to travel to Miami to

testify in U.S. court about a telecommunications

corruption scandal. His son, Patrick Joseph, was already in U.S. judicial

custody and provided details on Aristide’s telecommunications corruption in

Haiti. Two days before Venel’s

trip, an article appeared in the Miami Herald revealing what he was going to do,

and Aristide had him executed.

For me, and I imagine all listeners, hearing

what this woman went through with her kids in Haiti, the sheer terror they

faced, and their subsequent struggles to adapt to life in a foreign land was

heartbreaking. When she was asked

how she survived, she said her faith was key.

In addition to recounting the facts, she talked openly about

the deep emotional impact the murder and subsequent political persecution had

on her children. The kids faced

mockery from their schoolmates based on rumors surrounding the murder. She said her kids would hang their

heads in shame. With this court

ruling, her kids can lift their heads in pride for a father who was a political

hero; a man who never backed down in the face of threats and bullies. He stands in the company of Haitian

greats like Sylvio Claude and Jacques Roche who fought for their people and

never backed down. Bernard was a

man of principle. As Winston

Churchill once said – “if you have enemies, it means you stood up for something

in your life”. Bernard did just

that. Unfortunately, his enemies

made him pay the ultimate price.

In the end, this is a hollow victory, she said. Despite the conviction, they can never

return to their home while Aristide remains in country.

-3.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)